Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): A Primer

New clients often ask me “what techniques do you use?” They want to understand more about the journey they are about to embark on. Like many clinicians, mine is an eclectic approach, drawing on a range of modalities and applying them depending on the circumstances in the room at any given moment. In a response to this desire for knowledge and in an attempt to elucidate the theories and methods of some of these psychotherapeutic techniques, this blog begins a series, with an introduction to a particular modality followed by its application to a particular diagnosis.

This month’s focus is on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). True to its name, ACT is an acceptance and mindfulness-based technique that encourages commitment and change processes to create psychological flexibility. It draws on traditional behavioral and Gestalt models while also incorporating nontraditional therapeutic models like Zen Buddhism. It is theoretically grounded in Relational Frame Theory, which posits that our minds automatically use language to create relationships between stimuli.

ACT proffers that “pain is inevitable; suffering is optional.” It takes a notably different approach than some other modalities in this regard – it does not focus on symptom reduction, instead suggesting that our attempts to avoid our inner experience is what leads to greater distress in our lives. This experiential avoidance attempts to control or “get rid of” difficult internal experiences, by suppressing or trying to alter our thoughts/feelings/sensations. The issue is that the more we attempt to rid ourselves of experiences, the more those very thoughts and feelings appear. A common ACT exercise is to instruct, “Try not to think about a pink elephant.” No matter what you do – most end up thinking even more about the elephant; some focus intently on another word or object to distract – our mind is oriented around the pink elephant. Similarly, our mental and emotional energy becomes hijacked by our attempts to escape uncomfortable thoughts, feelings and sensations. It’s important to note that such avoidant behavior can ‘work’ in the short term. It’s what keeps us coming back to it. Research and experience teach us, however, that in the long term it is not effective. It’s exhausting and effortful; increases the activity of our sympathetic nervous system; does not change the quality of our negative thoughts and feelings; and most significantly, it pulls us out of our lives. Perhaps not surprisingly, avoidant behavior is correlated with a host of mental health issues.

Cognitive fusion is a primary cause of experiential avoidance. Cognitive fusion occurs when we take our thoughts literally. We make associations with events (see relational frame theory) and, instead of paying attention to what is actually happening to us in any given moment, we identify with established verbal representations and relationships. Our minds evolved to protect us from danger by performing these very processes – categorizing, evaluating, planning, predicting, making judgments and so on. They’re by no means a ‘bad’ thing. However, our mind engages in these processes so unremittingly that it can cause us to take in thoughts as reality. For instance, if you might have the thought “The last time I went to the store, I had a panic attack, so it is bound to happen if I go back again.” As a result, you might avoid going to the store. You start to believe that grocery store=panic attack.

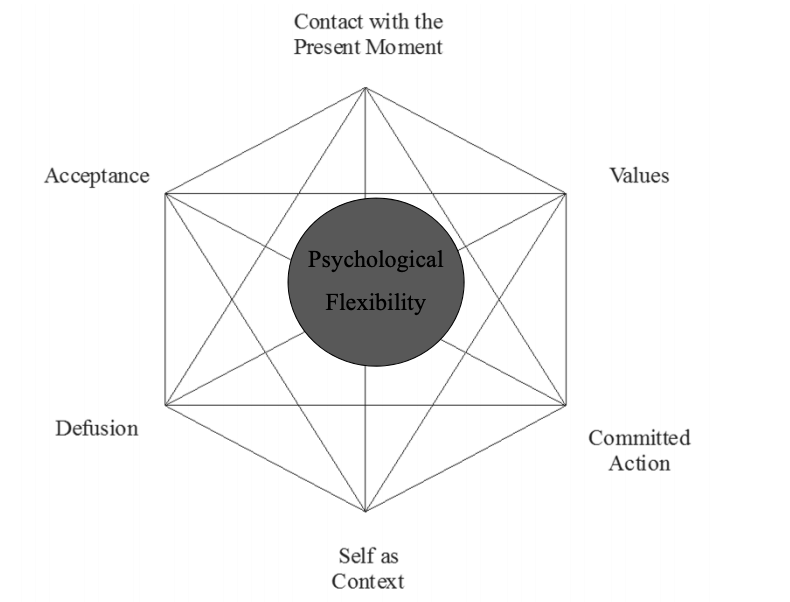

So what do we do with this information – if the focus of ACT isn’t symptom reduction, what is it? The goal of ACT is psychological flexibility, which is centered around six processes, as depicted below:

These six elements are guided by an acronym based on the modality itself. The first is acceptance, which refers to mindfully and non-judgmentally acknowledging what we are already experiencing. It is the opposite of a control agenda and avoidance, instead gently embracing thoughts, feelings and sensations as they arise. Cognitive diffusion assists in this practice by broadening our attention and de-literalizing thoughts. The idea is that having a thought is different than buying into a thought. Simply stating “I’m having the thought that ________________” creates some distance from the thought itself. We identify our mind’s evaluations while detaching from the content of our internal experience. Instead, we connect to the context in which these ever fluid and changing experiences occur (self as context). The goal is to see things as they really are, in the present moment (i.e. a thought is just a thought).

The second step of the ACT acronym is choose – choosing a direction for our lives. The direction is grounded in our values. Values are unique to each person; they tell us what we want our lives to be about. They’re qualities of purposeful action that can only be felt, experienced and deeply desired. Importantly, they are lived in the here-and-now (NOT the future!). They’re different from goals, although goals can be used in service of our values, as described below. One ACT exercise to identify values is to imagine your retirement party or funeral. What do you want people to say about you and what do you want your life to have stood for? A value driven life shifts the focus to living well vs. living to feel or think well.

The third step stands for take action – committed action toward realizing our valued life goals. We learn to behave in ways that move us forward in this direction. ACT has a phrase that “outcome is the process through which process becomes the outcome,” meaning that living out our values is ongoing and simultaneously a process and an outcome. There isn’t a finish line to reach. We continue to define goals based on our values and act in accordance with these goals, making space for psychological barriers along the way. We acknowledge that a range of thoughts, feelings and sensations will accompany us along the way, and choose to relate differently to them – mindfully engaging in this moment and in service of our life goals and aspirations.

As you read this content, you are likely having thoughts as evaluations arising. You might even be thinking “this wouldn’t work” or “it feels to overwhelming” or “this isn’t what I thought therapy was about – I want to control my feelings.” ACT would suggest that this is exactly what our minds do and invite you to hold these thoughts lightly, letting thoughts be what they are and do what they do. You might also reflect on how fighting thoughts and feelings has worked out in the past, how doing so sucks up time, energy and effort that could instead be channeled to living your most vital life. What would happen if you tried something radically different instead?

I will leave you with what ACT deems the “life question” to ask yourself: Am I willing to take all that life offers and still do what matters to me? If the answer to this is yes, then you might consider how Acceptance and Commitment Therapy could make a difference in your life.

Kroll, S. (2018). PESI, Inc. Acceptance & Commitment Therapy for substance abuse, eating disorders, anxiety, depression, self-injury, PTSD, psychosis, and more.